Photography by Laird Kay

In the bright window of a Toronto design store, an impossible city rises. Its towers — striped, slotted, and softly iridescent — seem to breathe with light. They tilt toward one another, forming a skyline that feels both futuristic and familiar, like a dream of downtown rendered in color theory. A passerby slows, drawn first by curiosity and then by recognition. These are not steel and glass. They’re LEGO bricks — hundreds of thousands of them — stacked into a utopia imagined and built by Raymond Girard, the artist behind Pen & Brick.

Girard’s work hums with contradiction: playful yet architectural, orderly yet emotional. His cities shimmer with the optimism of childhood and the discipline of a draftsman. His towers are both otherworldly and strongly aligned with patterns in the built environment, always with a creatively intentional twist.

Girard has the sincere warmth and confidence of an artist in his element, and he doesn’t mince words: “LEGO saved my life three times.” The act of stacking bricks is a through-line across decades of reinvention — a three-act architecture of life.

There's more! Continue reading this article by signing in or become a BRICKA subscriber.

Or sign-up to get digital access to Issue 1 for free.

Act 1 — The Flat Horizon

Setting: Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Girard grew up in Winnipeg, Manitoba, “the flattest, most treeless place you’ll ever see,” he says, laughing. “From a really early age, I just remember thinking, there’s got to be more to life than this horizon.” In the endless cold, he discovered a kind of longing for variety and verticality.

Television offered escape. “I’d wait for the opening credits of Green Acres,” he recalls. “Eva Gabor runs out onto her terrace, and you see the New York skyline behind her, that cluster of towers. I thought, ‘What are these big beautiful tall buildings everywhere?’” Before he could reach Manhattan, he built his own. Encyclopedias became skyscrapers, dollhouses became apartment blocks. When the dishes started stacking up into makeshift cities in the kitchen, his parents intervened with a small box of LEGO bricks — a splurge they could barely afford. “It was the best thing they ever did for me. I played with my bricks for days on end.”

LEGO became both playground and protection. The brutal winters and his asthma kept him inside. He felt isolated at school and often pretended to be sick just to stay home and build. “LEGO was my respite from all that. LEGO saved my life in a way — it basically allowed me to create this whole little world.”

He never outgrew that sense of structure as solace. In school, while others solved equations, Girard filled his notebooks with sketches of towers. Math eluded him — but proportion did not. The logic of the grid, the rhythm of repetition, the patience of stacking: all of it became creative instinct.

Act 2 — The Stress of Success

Setting: São Paulo, Brazil

If childhood gave Girard imagination, adulthood tested it. He never stopped sketching, but LEGO gave way to studying architecture, and eventually, he realized he enjoyed the scale of interiors. He earned a degree in interior design, but recession after recession in Canada made creative work unsustainable. “I’d design these great spaces and never get paid, or get paid very little.”

He pivoted. A small editorial project — publishing a magazine for Air Canada — led to a 27-year detour in creative direction, marketing, and publishing. “I got lost on my way to the drafting table,” he jokes. “But I have no regrets because it was wonderful, it allowed me to travel. It allowed me to see the skylines of the world.”

Girard wasn’t building, but he never stopped sketching — drawing towers during hours-long conference calls. Then came São Paulo. Traveling for a joint venture with a marketing agency in the city, Girard was on a late-night taxi ride through a rough part of town. They found themselves surrounded by motorbikes, their riders armed with guns and swarming. “I almost got shot that night, but it was almost surreal — like what’s happening here? In the days that followed, I realized the gravity of the situation and had a bit of PTSD.” The stress of the job and that night became overwhelming.

Back home in Toronto, his husband Laird intervened — with LEGO. He handed Girard the LEGO Architecture Farnsworth House. Click, click, click. “I was like, ‘Oh, that sound.’ I think there’s something about the sensory nature of LEGO,” recalls Girard. “The pour out of the box, the rattle in your hands — it’s beautiful.” He started playing, “LEGO saved my life again — it was the therapy I needed.” One set led to another, then another, but it wasn’t enough. Then came the Pick-A-Brick Wall at the LEGO Store. He filled a few canisters. Then a few more. “I just had this need to stack.”

Towers took over the entire basement — 600 towers of every height and hue. Some measured 24 inches, others seven or eight feet. At one point, Laird, himself an aviation photographer, told Raymond to arrange them into a skyline, and he’d photograph them like a plane flying over a city. Laird planned to take the photos while Raymond was at work; what he didn’t plan for was his tripod knocking over a tower, and the city-wide domino effect that ensued. The entire skyline collapsed. “I call it my Chicago Fire,” Girard laughs. “But it taught me to build better.”

Interlude — The Art of Pen & Brick

If the basement skyline was catharsis, Pen & Brick was evolution. The name nods, of course, to his sketching and building, from the two sides of his brain: designer and builder. He begins each piece either from a sketch or dives directly into the bricks. “The two-by-four brick is my module. I know those proportions and that system and grid. Then I take it as far as I can.”

Girard’s public breakthrough came when a design friend visited his home and saw his towers. “He said something like, ‘What the hell is all this?’” A Canadian department store called Holt Renfrew had asked him to curate a wall in their store — every quarter they installed new art in their Wonderwall. “He asked if I could install it in the store, and because I’m an idiot, I said, ‘Sure, I can.’” Girard moved his basement city to the store — along with scaffolds, acrylic sheeting, and a sense of terror. “I hadn’t pulled an all-nighter since design school,” he says.

The two-story LEGO Metropolitan installation was a riot of color and density, a miniature metropolis glowing under retail lights. Hundreds of slender LEGO towers rising in stripes of cobalt, coral, chartreuse, and rose. Viewed up close, it feels less like sculpture and more like composition — a symphony of repetition and variation. The eye moves from the candy-colored facades to the glowing white spires.

For Girard, it was a revelation: people loved it. “It made adults stop and smile,” he recalls. Press coverage followed. So did commissions.

One of those commissions came from a curator at a children’s hospital in Hamilton, Ontario. The brief: design an artwork for the prosthetics and orthotics waiting room. The result spanned 24 feet wide and six feet high — a glowing skyline of colorful, vertically patterned towers threaded with light. Girard designed Kaleidoscope City so that children in wheelchairs, on crutches, or lying on stretchers would each have a distinct view. “Hospitals forget ceilings,” he says. “But when you’re on your back, that’s your world.” He hid surprises at every level: sharks, tiny arches, hidden patterns of color. “It’s something new to discover as they grow.”

The success of Kaleidoscope City opened doors to galleries and design spaces eager to see how far LEGO could go as an architectural medium. The 2018 installation Block Party at Akasha Art Projects in Toronto marked another evolution in Raymond Girard’s exploration of architecture, play, and spatial experience. What began as a simple idea — “Why don’t I do a takeover for the holidays?” — became a full-gallery intervention where LEGO towers didn’t just sit on pedestals but inhabited the space. Colorful, vertically patterned columns rose from the floor, wrapped around beams, and extended up the mezzanine like a living structure. The effect was both architectural and animated: candy-colored “tentacles” of brick weaving through the gallery’s minimalist white interior, creating a joyful tension between precision and spontaneity.

Viewed from the street, the installation appeared to burst out of the gallery — a skyline unbound by the frame of the window. Inside, the work surrounded visitors in a rhythm of color and pattern, transforming the gallery into a playground of geometry and light. He exhibited again at Akasha in 2019 — this time, Girard’s immersive bricks were united with his pen-and-ink sketches.

Always looking to activate street-level architecture, Girard filled the window of 313 Design Market with a kinetic city for Toronto’s annual design festival in 2020. For Toying with Utopia, Girard’s structures actually moved. Buildings glided on concealed tracks, reflecting and refracting in the glass.

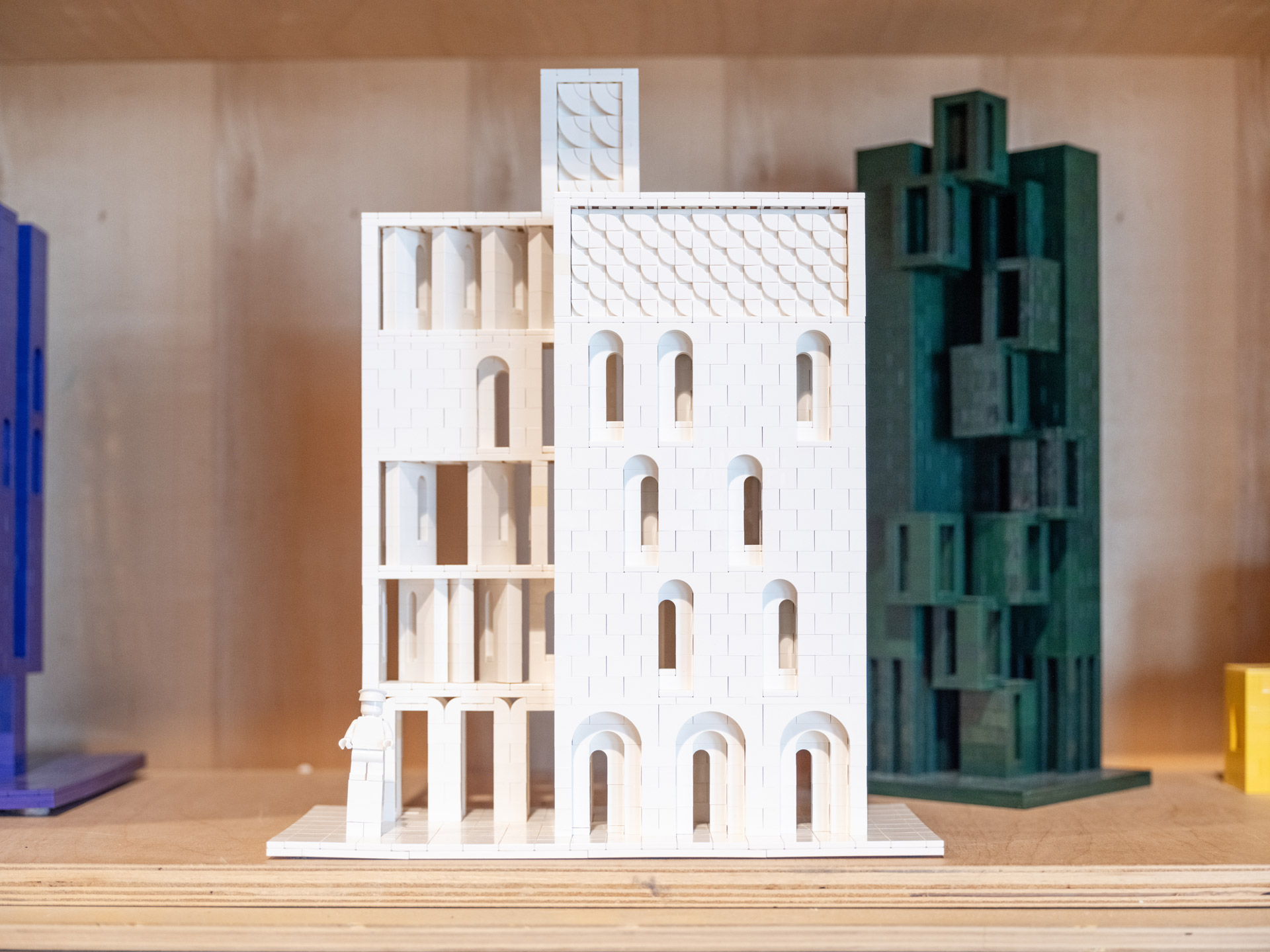

Travel forced Girard to work small. He began filling his carry-ons with bricks of a single color, building architectonic sculptures on the go. Each piece became a fictional, monochrome building in the city within Girard’s mind — a study in form, proportion, and restraint. To his delight, architects and collectors began acquiring them. In 2024, he exhibited a collection of 28 of these structures at Filter Design.

Girard has a consistent design language that he constantly pushes — or stacks — to explore. He pushes his technique as well, but only to a point. “I just like stacking. I think that goes back to that very early instinct, as a four-year-old, just stacking and seeing how high I can go.”

Color, once his fear, is now his signature. “In design school, I only used black and white,” he says. Fashion changed that. Studying Missoni, Etro, and Fendi taught him how contrast creates sophistication. “A lot of my towers are straight-up copies of their colorways,” he laughs. Travel sealed the shift: Lisbon’s tiled facades proved that bold color can be elegant. “Our cities are too dull,” he says. “You can have beautifully colored buildings.”

The 2x4 brick may be his module, but Girard clearly loves arches. And that interplay between the rectilinear verticality and the perfectly geometric arch, so prevalent in real-world architecture, is what keeps our imagination just slightly tethered to reality as we explore Girard’s made-up metropolises.

Act 3 — Crash, Cast, and Recovery

Setting: Toronto, Ontario, Canada

By 2022, Girard was ready to quit corporate life for good. He gave notice, planning to take a year to define a LEGO-based immersive-experience business built around his unique artwork. A week later, while cycling on a seemingly deserted suburban street, a car hit him.

He woke up in the trauma unit. “They told me they might have to amputate fingers on my right hand.” His mind leapt to LEGO. “All I could think was, how will I build? It’s just so central to who I am.”

He spent weeks immobilized — left arm in a sling, right hand in a cast, only thumb and index finger free. “I told Laird, go home, bring me LEGO.” Laird brought bricks to the hospital, and LEGO saved Raymond a third time. “I built tiny things on the hospital tray. It was such a relief. Click-click-click. I was me again.”

The recovery was long. His hands don’t cooperate as well as they used to. “They glitch sometimes,” he says. “I drop a lot of bricks.” But that, too, has become part of the work — the acceptance of imperfection, the beauty of persistence.

Epilogue — The City Within

Today, Girard splits his time between a space in Toronto, housed within the custom design-build firm Ben Homes’ facility, and a studio in the Alentejo region of Portugal, near Lisbon. The latter sits near Portugal’s famous marble quarries. “I want to make my own building elements,” he says. “Scale up LEGO proportions in marble — Duplo-sized, permanent, outdoor.” He imagines walk-through, brick-built sculptures dotting a hillside: tactile, larger-scale architecture for adults and children alike.

Raymond has built a life of LEGO, his cities delight in their juxtaposition between abstraction and colorful whimsy — but they persist in our minds because they nudge us to dream.

When I ask him what happens inside his utopian cities, Girard pauses. “When I was a kid, I just imagined everyone was happy there,” he says. “Everything’s bright and tall — it’s never boring, there’s always something to look forward to.”

Look closely at his skylines — at the arches and colorways, the balance between order and play — and you’ll see that optimism made real. In Girard’s hands, the humble brick becomes a manifesto: dream big, build up, never stop stacking.