Photography by Mads Prahm

Images courtesy of Light Brick Studio

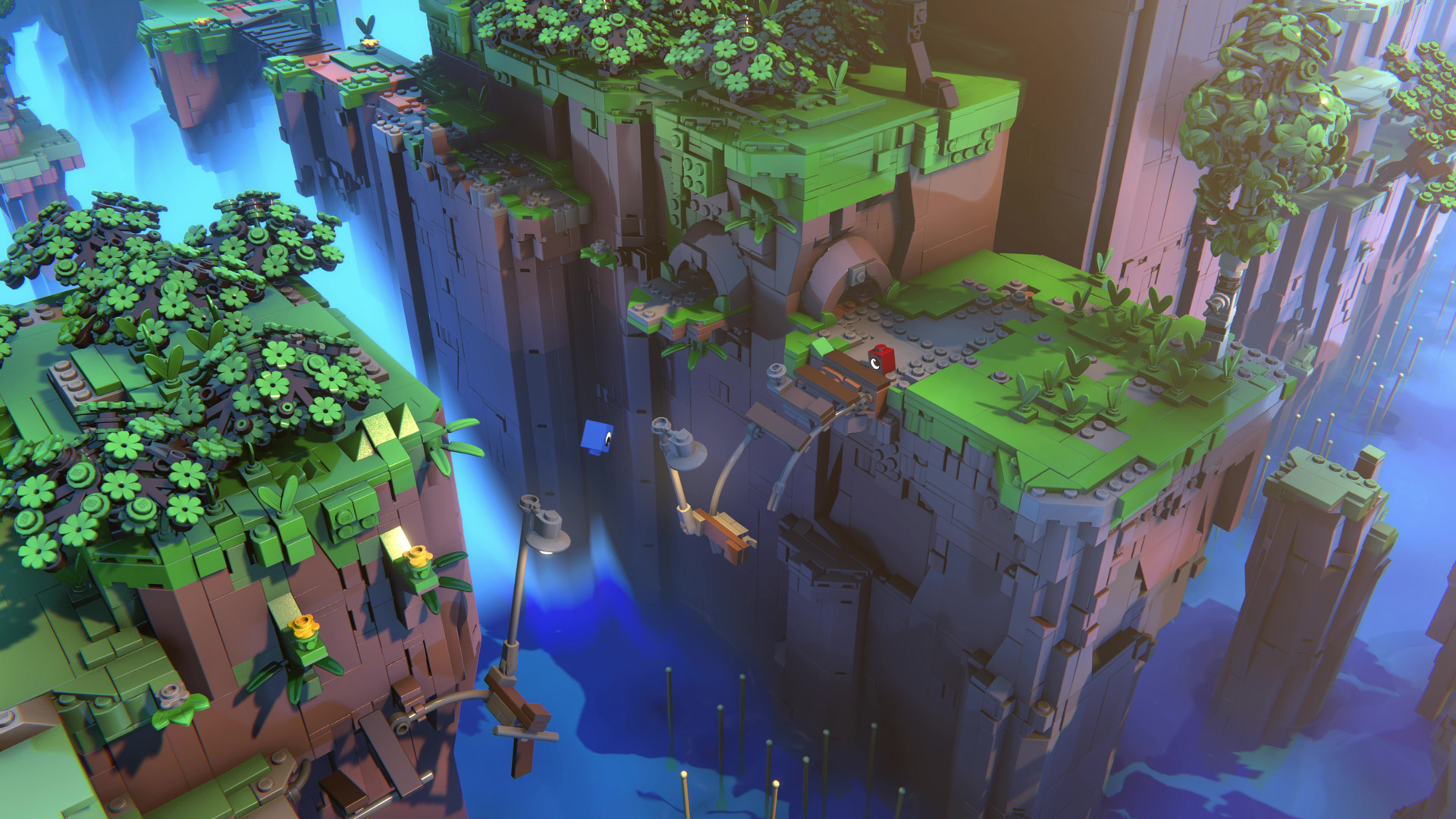

Two bricks stare at each other across a small gap in a bridge. They wobble, they tumble, one falls. The other hops forward, then back, until the studs align and click — a sound so subtle and satisfying it could only come from LEGO.

On my couch, my eight-year-old daughter and I laugh out loud. Not a funny laugh, but the kind of unguarded laugh that bursts out when delight sneaks up on you. We’re not controlling a minifigure or a human avatar — we’re the bricks themselves, rolling and tumbling across luminous landscapes in LEGO Voyagers, a game by Copenhagen’s Light Brick Studio. The moment feels strangely real. In learning to cooperate on screen, we’ve stumbled into a conversation about connection, patience, and play.

This is Light Brick’s gift: to build games that feel like LEGO, not because they’re branded that way, but because they embody the philosophy that has animated the LEGO Group for generations — helping us rediscover what it means to build, together.

There's more! Continue reading this article by signing in or become a BRICKA subscriber.

Or sign-up to get digital access to Issue 1 for free.

When Bricks Become Pixels

In our current video game era, where cinematic cutscenes and motion-captured heroes rule the day, Light Brick Studio takes a different path. Their games — LEGO Builder’s Journey and LEGO Voyagers — don’t cast you as a caped crusader or master Jedi. Instead, they hand you the humble LEGO brick.

Founded in 2019 as a spin-out from the LEGO Group, Light Brick is an independent studio devoted entirely to exploring the creative and emotional potential of the brick itself. The team is small — a few dozen artists, designers, and engineers — but their mission is vast: to see how far a single system of interlocking parts can go in evoking curiosity, empathy, and joy.

The studio’s creative director, Karsten Lund, embodies that mission. He grew up in Copenhagen, splitting his time between LEGO sets and the arcade at Tivoli Gardens, where flickering pixels felt like windows into another world.

“I owe a lot to the LEGO system for my creativity,” shared Lund. “My understanding very early that things can be taken apart and put together in new ways, and you can always reconfigure, and you can always design and build your own world around you.”

Lund started his video game career in the 90s in Denmark, making games for the Sega Genesis, then eventually got a chance to work at IO Interactive, the largest AAA studio in Copenhagen.

“Video games were fascinating to me from a very early age. Even before I had my own computer, I would cut out characters from cardboard and make my own sort of games with a dice roll to simulate play.”

At IO’s sister studio in Montreal, he dove into the new world of mobile gaming, launching games like Hitman Go and Lara Croft Go — with a wealth of possibilities in that new gaming medium.

Two years later, a lifelong dream became a reality — Lund joined The LEGO Group as creative director of the games department. At that time, it was more about partnering with other game studios to make various LEGO-branded games. “Our goal then was to make sure everything was on brand and high quality and made sense for the portfolio. And I think after six years there, there was an opportunity to set up a small experiment and develop games ourselves, which was the start of our LEGO Builder’s Journey adventure.”

Building Builder’s Journey

When LEGO Builder’s Journey debuted in 2019, it didn’t feel like any LEGO game before it. There were no instructions, no dialogue, no missions. Players simply moved bricks, piece by piece, through a wordless parent-and-child narrative told entirely through motion, light, and the quiet click of bricks.

As he recalls, “LEGO had a lot of great games coming out, but I just had this one question, ‘what would it feel like if building with bricks was the thing in the game?’ I just had this nagging feeling that it must be possible.”

Lund brought his experience in mobile gaming to the challenge of bringing a new type of LEGO game to life. Inspired by LEGO dioramas, LEGO Builder’s Journey was initially designed for mobile and leaned heavily into the tactile intimacy of touchscreens. Apple’s iPhones at the time were sporting a new feature, 3D Touch, which used pressure sensors to register multiple levels of force. Simply touching the screen was one input; touching and pressing harder was another.

Early prototypes of Builder’s Journey used Apple’s “deep touch” feature to simulate pressure — you’d press a little harder to seat a brick, and the phone would respond with a subtle vibration nudge. The illusion was uncanny, like tapping into muscle memory. But when they tested it, no one understood what to do. The magic was lost in translation, or perhaps the feature was too new.

“Everybody loved it internally in the studio and in the broader game team at the LEGO Group. Then we showed it to users, and nobody understood it. Nobody got it at all. I mean, nobody. It was one of the biggest sort of reversals I’ve ever experienced making a game.”

For many teams, that might have been the end of the experiment. For the internal team at LEGO, it was just the beginning of pivoting, testing, refining, and testing again — with weekly new users in their studio. The team would watch over the playtesters’ shoulders, feeling their pain and frustration — then they’d adjust the game and do it all over again.

Testing helped hone the story as well. Karsten and team were committed to making it non-verbal, but when playtesters completed the game and recounted what they believed the story was, their stories didn’t match what the team was trying to tell.

“We just sort of gave up and said, okay, they don’t need to understand the story. We’re just going to make our story, we’re going to polish it up. It’s a poem,” said Lund. Then all of a sudden, with everything polished — graphics, gameplay, controls, music — it all clicked together. “All of a sudden, the playtesters were like, we get it now, and that was a really great moment.”

In the finished game, you guide a small brick child across sculptural, diorama-like landscapes — rivers, bridges, foggy valleys — in search of a parent figure who always seems just out of reach. The puzzles are environmental and meditative, built from jumper plates and tiny stacks of bricks that serve as both pathway and metaphor. There’s an unspoken story of separation and reunion, but it never tells you exactly what to feel. Instead, Builder’s Journey invites you to project your own meaning onto its world — to read your own memories, your own longing, your own sense of creation into the quiet space between bricks. Like building itself, the story only completes when you place the final piece.

The Studio

That early success — the sense that something so small could carry so much feeling — became a turning point. The team had proven that a LEGO game didn’t need IP licenses, instructions, or dialogue to move people; it only needed the honesty of creative play.

In 2019, with the blessing of — and even some investment from — the LEGO Group, Karsten and a small crew spun out to form Light Brick Studio, an independent studio dedicated to exploring that magic further. They carried with them not just the technology and lessons from Builder’s Journey, but a philosophy: that the humble brick, in all its simplicity, still holds infinite potential for storytelling, creativity, and human connection.

Light Brick’s culture mirrors the system it celebrates. There’s structure, but it’s modular. Ideas emerge bottom-up from any designer or developer, and leadership’s role is to “bind the bouquet”—to gather the best fragments and arrange them into coherence.

Every prototype begins abstractly — a weird mechanic, a color test, a physical property to explore. Playtesters get invited early — often weekly — with one unspoken rule: if the room isn’t filled with laughter or surprise, it’s back to the drawing board. “We do lots of interesting, creative risk-taking prototypes, get some players in, try to understand what they understand about it, and try to sort of reflect that into the project. We have audience members at the table at all times,” said Lund.

In that sense, Light Brick functions less like a traditional studio and more like a community of playful researchers. They experiment constantly — even their team rituals are built around play. Each summer, the team pauses production to design garden games — analog experiments that remix classics like croquet or bocce with new rules, constraints, or materials. The point isn’t competition; it’s creative rejuvenation.

This spirit carried directly into LEGO Voyagers, a project that began, as most Light Brick projects do, with a question.

To Be a Brick

It started with one developer asking, “What would it feel like to be a brick?”, then prototyping an answer: a rectangular solid rolling across a gray test level. No universe, no art, no level design, or music; just a simple virtual space and a small rectangular cube. The control felt awkward and unpredictable — too much inertia, too little precision — but somehow charming. Then they added a second brick.

“We wanted to do something we’d seen organically happen in Builder’s Journey,” recounts Lund. “People played it together even though it wasn’t a multiplayer game. They’d sit together and say, ‘I’ll try this or let’s try that.’”

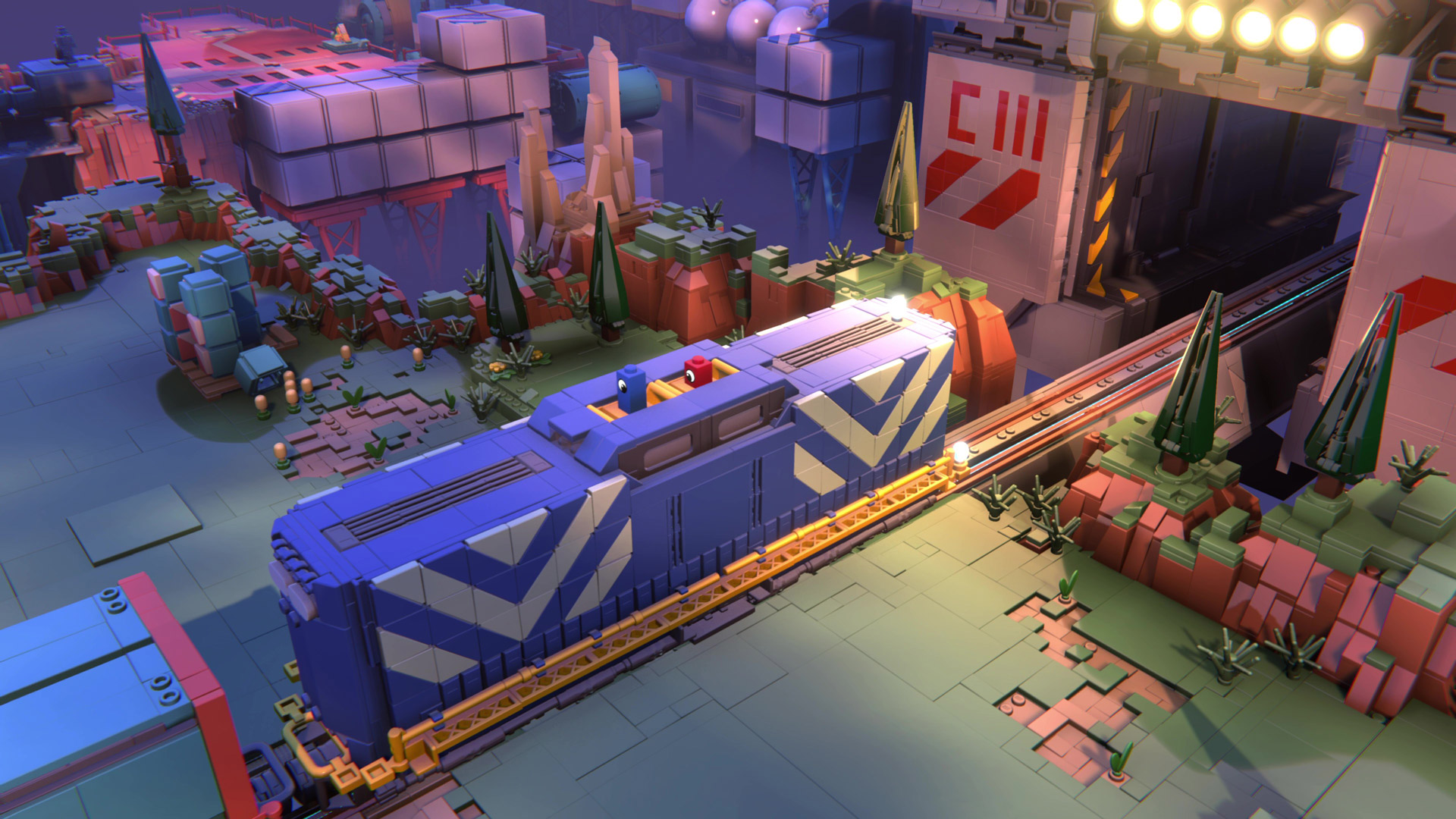

So they decided to lean into that approach and make Voyagers a two-player game. With a second brick in the grey-box prototype, something magical happened. The two shapes bounced off one another, collided, and began to collaborate. The studio’s playtest room filled with laughter. Players started speaking aloud to each other: “You jump.” “I’ll hold this.” “Try attaching here.”

It wasn’t just fun — it was revealing. When two players cooperate, they narrate their process. Designers could literally hear their intentions and frustrations in real time. It was a kind of design direction through conversation. The team realized they were observing something more profound than a game mechanic. They were watching social physics: how people negotiate, share control, and recover from failure — how friendship itself operates.

That discovery became LEGO Voyagers — a new cooperative adventure about connection, framed through two wordless characters who are, quite literally, pieces of the same system, working together as friends on a journey through their world.

If Builder’s Journey was a poem, Voyagers is a duet. There’s no dialogue, no subtitles, no exposition — only the faint bleeps and clicks of the bricks themselves.

The studio’s approach to storytelling is less cinematic than sculptural. They start with a theme — in this case, friendship, shared dreams, and the bittersweet moment when paths diverge — and let the level design express it. Each act unfolds like a miniature fable set to ethereal, playful music: the bricks meet, explore, separate, and reunite. You don’t read the story; you perform it.

This approach demands enormous discipline. Without words, every cue must be visual or tactile — a slope that invites jumping, a color shift that signals loss, a moment when both players must attach to proceed. The team calls it “show, don’t tell,” taken literally.

But their philosophy runs even deeper. By refusing to explain, Light Brick puts players in the same learning loop that defines LEGO play itself. You don’t get a tutorial when you dump a pile of bricks on the floor. You experiment. You fail. You adjust. And in that process, you learn.

That, for Light Brick, is the story. Playing Voyagers with my daughter reminded me that the real drama isn’t on screen — it’s between us.

Every puzzle sparks a new negotiation.

“Wait, I think we have to stack!”

“No, no — push me first.”

We argue, laugh, cheer. She falls off a ledge and howls with mock despair. I rescue her and become the hero — for about ten seconds, until she returns the favor.

Through its gentle physics and quiet rhythm, Voyagers externalizes emotions that most games keep hidden in dialogue trees. Cooperation, frustration, forgiveness — all of it becomes visible.

This is where Light Brick’s design philosophy shines: the system creates the story, but the players complete it. Lund explains that this approach asks more of the player’s imagination — and rewards it in return. “When you build a LEGO model,” he says, “even if you didn’t design it yourself, your brain still takes ownership of bringing something into the world. You’ve interpreted it, you’ve made it real. That’s what we tap into in our games.”

With Voyagers, the process and earning that credit doesn’t just happen in your head — it happens in the world Light Brick Studio built and in the room, in real life, as you play together.

Building the World

Look closely at Voyagers’ environments and you’ll recognize the unmistakable language of AFOL-level craft. Every detail — from the way loose bricks scatter to how translucent elements catch the light — echoes the grammar of physical building.

During development, the team evolved their grey-box prototypes into simple, grey versions of each level — rough forms built from placeholder parts. Then, over the course of months, a group of expert LEGO modelers — including LEGO Masters champions and former LEGO employees — rebuilt the detailed world brick by brick in digital space.

By the time they finished, the world contained more than 1.7 million digital bricks. Each one placed by hand in virtual space.

Density is a delicate balance: too few studs and the illusion breaks; too many and the player gets stuck. That friction isn’t cosmetic — it’s gameplay. Each stud is both a visual cue and something to interact with — the little bricks you control can click to any stud they can reach.

At Light Brick, art and engineering are inseparable. The lighting, camera, and sound design all contribute to the sensation that this tiny world could exist on your table and that these two little 1x1 bricks are truly friends. The goal isn’t realism; it’s recognition. You’ve seen these pieces before. You know how they feel. When it all comes together — the click, the light bloom, the quiet background hum — you see only the craft of a unique LEGO world.

Underneath Voyagers’ visually elegant world lies a mountain of engineering complexity. A physics-based multiplayer game with attachable parts sounds simple; in practice, it’s chaos. Predicting collisions, syncing two players’ movements, tracking hundreds of loose bricks in real time — it’s a nightmare of math.

But the chaos is part of the point. Light Brick doesn’t want perfection. They want believability. A real pile of LEGO is unpredictable. Bricks slide, catch, topple, and surprise you. That’s part of the joy.

In Voyagers, you feel that same edge — the moment where control meets freedom. When your brick tumbles one way too far, it’s funny, not frustrating. The physics behave like a conversation: responsive but imperfect, alive in the gaps between intention and outcome. That slight unpredictability is where the play lives — where the adventure these two brick friends take gets propelled across the studded landscape.

Building What’s Next

Together, Builder’s Journey and LEGO Voyagers mark a turning point in LEGO’s digital evolution — a quiet rebellion against the licensed, combat-driven formula that long defined LEGO video games. Instead of parodying blockbusters or leaning on brand nostalgia, these games center the act of building itself as a storytelling mechanic. They translate the tactile poetry of bricks — connection, iteration, repair — into an emotional, playable form.

Where Builder’s Journey distilled that intimacy into a single-player meditation on creation and connection, Voyagers expands it into a cooperative experience, transforming digital play into a shared act of empathy. Together, they signal a shift: from LEGO games as entertainment products to LEGO experiences as interactive design, rooted in the same philosophy that has guided the brand into our hearts and minds.

Lund insists Light Brick Studio is not done with the brick — their curiosity is expanding. Future prototypes explore different genres, different forms of cooperation, and different ways of telling stories without words.

Whatever comes next, it will follow the same principle: a world that feels both fresh and strangely familiar, where the logic of play invites reflection on what it means to create, connect, and care. Light Brick isn’t chasing trends or licenses. They’re chasing truthful play — the kind that reminds us who we were before we started worrying about winning.

Lund sees their future, “I would love to use technology to facilitate free play — the lost art of playing freely without objectives, inventing the rules and ideas as we go along, much like children or even animals do — building play as they go.”

As I continue the free play in Voyagers with my kids, the joy and delight are ever-present. Somewhere between our laughter and the sound of pieces clicking together, I realized what Light Brick Studio has built isn’t just a game — it’s a bridge. Between digital and physical. Between structure and spontaneity. In my case, between parent and child.

A reminder that the smallest acts of creation — placing one brick on another — can still carry the power to connect.